There are limits that can only be exceeded by agreeing to radically rethink one's way of thinking. In aeronautics, Airbus is pushing the limits through its aircraft engines, with a design change deep within its turbines, essential to justify a fourth generation of single-aisle aircraft, the A320 family. To unveil the first building blocks, Airbus invited several of its managers in charge of this new vision to Toulouse for a round table.

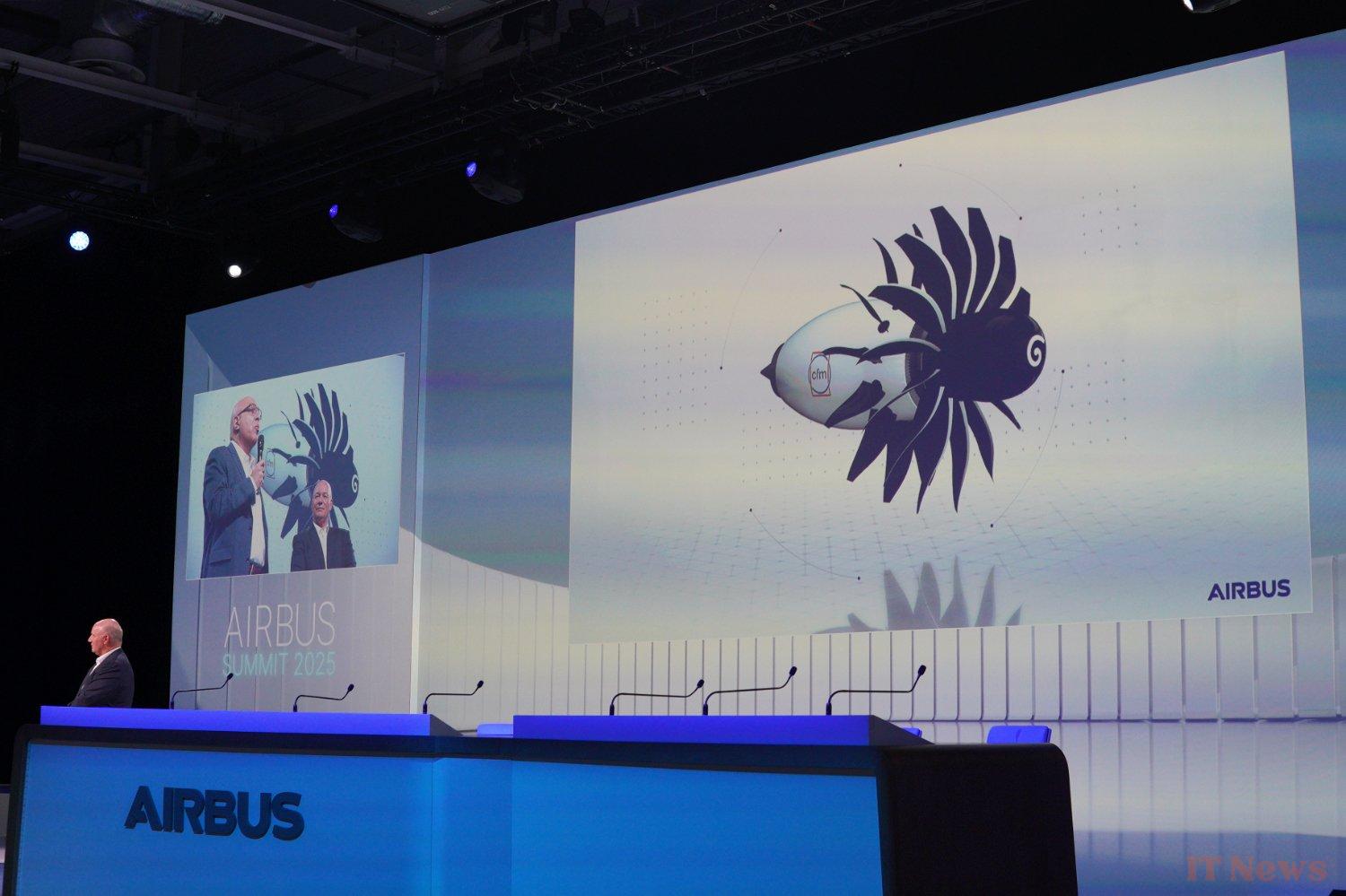

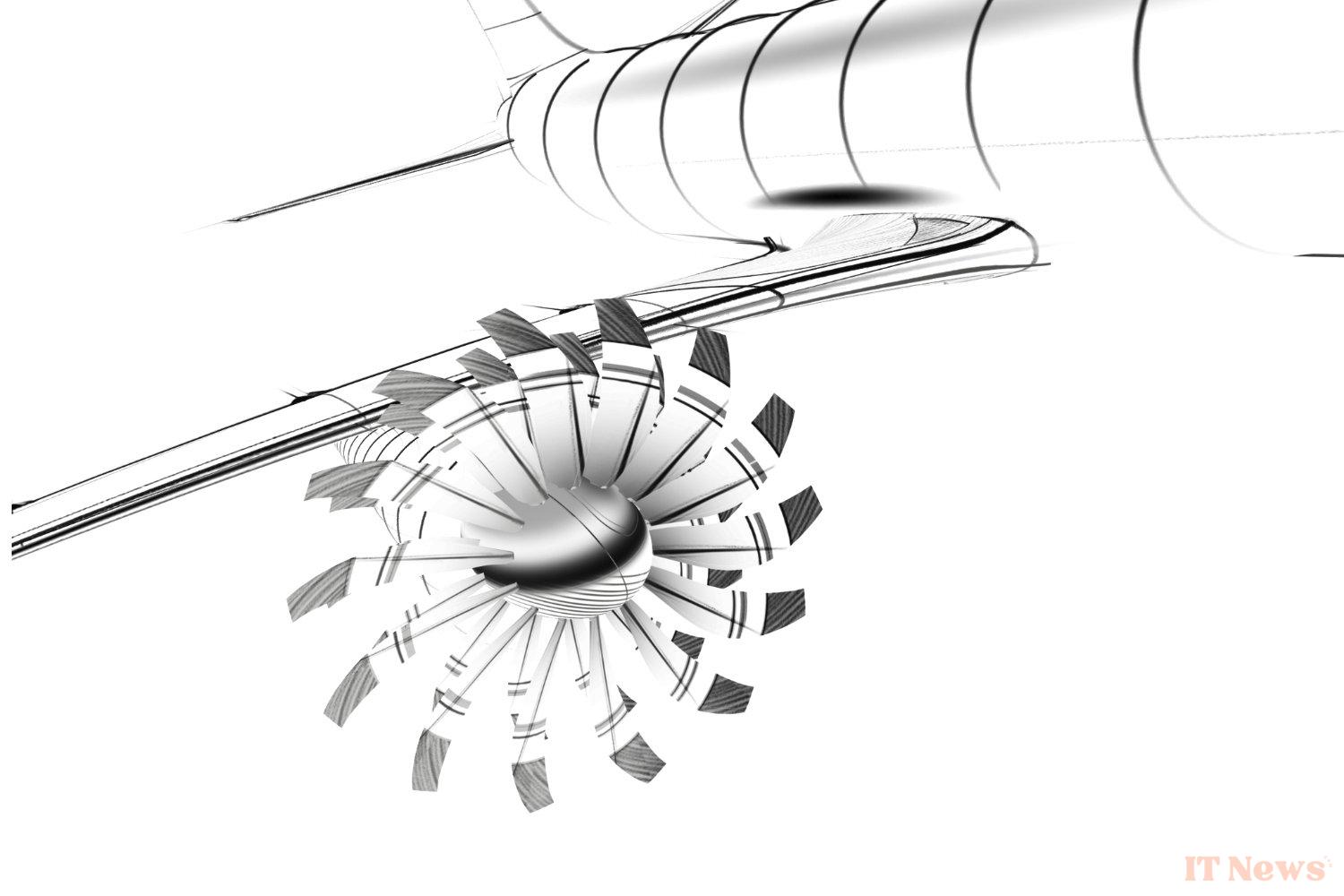

In parallel with work on the wings and the very structure of its aircraft, Airbus confirms its intention to switch to an "open fan" engine on its future next-generation A320. The latter is not planned before the middle of the next decade, but to get it flying by then, it will have to move quickly. Rather than following the same logic of a jet engine equipped with rotors integrated into a nacelle, the future "open fan" engine will eliminate the latter, to considerably enlarge the propellers of turbofan engines. A way to move more air, with less fuel, and lighter engines.

These jet engines will be placed under the wings, with a blade diameter that risks forcing the development teams to thoroughly revise their designs. With these open fans, development will require a lot of resources, as several constraints exist, particularly regarding safety and noise. On several occasions during its summit in Toulouse on March 24 and 25, Airbus left the door open to the possibility of pushing the engines to the rear of the aircraft, a device generally found on regional jets or in business aviation.

Airbus will not be directly involved in the design of this future open fan engine, for the fourth generation of its A320s. The aircraft manufacturer turned to CFM International, a joint venture between France's Safran and the American company GE Aerospace. In Toulouse, its director of operations and head of the Technology division, Mohamed Ali, stated that he was already working with the authorities to obtain certification for the new design, particularly on the issues of safety and noise management. Technically, he specified that the open-fan engine would rotate at a speed of 1000 revolutions per minute, three times slower than conventional jet engines.

Over the past seventy years, the aeronautics industry has already made progress in terms of efficiency, by reducing the proportion of kerosene in propulsion efficiency. Mohamed Ali specified that the ratio between thrust (propulsion) and fuel (kerosene) had gone from a ratio of 2/3 to 5/6 and then 11/12 in the 2000s. The open fan engine would overcome resistance on conventional engines and contribute to the 20 to 30% reduction in aircraft consumption expected on the future generation of aircraft.

Boeing late, but not absent

Despite the spotlight on the technology in Toulouse, the open fan engine has been no longer a secret since 2021, when CFM International launched the RISE (Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Engines) program. It is not, either, a European exclusivity, since the United States is also responsible for its development, with the work of GE Aerospace, but also Boeing, NASA and Oak Ridge National Laboratory – known for having worked on the development of the A-bomb.

Together, these American actors reiterated their interest in November 2024, when new work on modeling the engine using supercomputers was announced. At that time, the Department of Energy announced that it had exceeded 840,000 hours of work on virtual machines, through the INCITE program, giving them access to two of the three fastest supercomputers on the planet, Frontier (Oak Ridge National Laboratory) and Aurora (Argonne National Laboratory). The question is therefore no longer whether Boeing is also considering open fan engines for its 737s.

On both sides of the Atlantic, digital modeling has given way to wind tunnel work. In Toulouse, Mohamed Ali stated that the first tests were promising, with engines installed under the wings, in unusual tunnels. The longest of these is located in France, in the Alps, and in January began tests simulating flight conditions, at low atmospheric pressure and cruising speed. Other tests are planned to reproduce conditions at lower speeds, during takeoff and landing.

Regarding flight tests, Airbus is taking the lead. On March 25, the aircraft manufacturer announced that it will install an open-fan engine on an A380. The four-engine example is currently being used for flight tests of an engine running 100% on SAF fuel. It will replace one of its turbojets with an open-fan prototype, keeping the other three conventional engines to maintain a sufficient safety margin in case of a problem. The flight is currently scheduled for "the end of the decade", a few months apart from another test, this time on the ground, for an integrated hydrogen propulsion system.

0 Comments